What is United Front? Details on a race and implicit bias training program developing in Fort Wayne

Formed in response to last summer’s protests, United Front has been gaining traction in Fort Wayne and beyond. We explore its successes, challenges, and plans for the future.

When Iric Headley heard about the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and experienced the subsequent protests in downtown Fort Wayne, he felt the weight of pain and trauma.

“Being a Black man, I was really hurt by the killing of George Floyd and watching what was taking place—not only around the country, but in our city,” Headley says. “You could feel the pain that was on the Courthouse lawn.”

While Headley was processing this pain, he was contacted by Fort Wayne Fire Chief Eric Lahey, who wanted help enhancing the department’s internal diversity and inclusion practices. While Headley was grateful for Lahey’s leadership, he also felt exhausted by the impending conversation.

“Unwillingly, I got on that Zoom call,” Headley says. “I even kept my camera off.”

But on that call with Lahey and a few other Fort Wayne leaders, Headley met a scholar named Dr. Pascal Losambe, Ph.D., Co-founder and Chief Content Officer for Synergy Consulting Company, who teaches courses on race, reconciliation, and cultural competency.

“When I heard Dr. Losambe talk about race, I ended up taking two pages of notes, front and back, while sitting in a parking space in South Haven Michigan,” Headley says.

Rather than feeling weighed down, he found that Losambe’s teachings invited him to explore race and human interactions in a way he hadn’t experienced before.

“Dr. Losambe helps us understand how we, as individuals, arrive at the various places we end up, from a human, neurological, and psychological perspective,” Headley says. “That really resonated with me.”

Soon, Losambe’s teachings became the framework for more than the Fire Department’s internal diversity and inclusion efforts. In collaboration with Headley, Joe Jordan of the Boys and Girls Club of Fort Wayne, and a team of about 15 other local leaders, these teachings developed into a first-of-its-kind, city-wide initiative known as United Front.

The initiative utilizes the skills and talents of each United Front team member, as well as Losambe’s knowledge in brain science, psychology, and sociology to create role-specific conversations around race, bias, and other factors in Fort Wayne’s community. Program fees are subsidized by local sponsors and charged to organizations at various rates, depending on how many employees are participating. The fee for individuals is $150.

United Front’s goal is to provide structure to the often-nebulous process of addressing cultural differences in cities, businesses, schools, and organizations, which contribute to misunderstandings in social interactions. As communities across the U.S. attempt to prevent racially motivated attacks following Floyd’s murder, United Front is a training program designed to help them take an initial step toward getting there. That step is, essentially, getting residents of radically different backgrounds and beliefs to speak the same language, Headley says.

For Losambe, speaking the same language in a diverse community starts with creating a shared space where people can come together. Warm and gregarious, with hint of an African accent, Losambe moved to South Africa at the fall of its 40-year apartheid, seeing firsthand “the healing that needed to take place there.”

“It took Nelson Mandela coming in and saying: There is one side of this argument, and there is another, but what happens when those worlds collide?” Losambe asks. “What happens in that third space, where we need to coexist and be a community together?”

In a way, Losambe’s goal with United Front is to create a similar “third space” in Fort Wayne, where people of different backgrounds feel comfortable and willing to learn from others.

But while Headley quickly believed in the power of Losambe’s teachings, he didn’t think much of the Fort Wayne community would be interested in courses on racial bias due to the uncomfortable subject matter. When United Front began offering its courses in February, Headley assumed 20 organizations—maybe 500 people total—would sign up.

“That was our goal,” he says. “Six months later, more than 8,300 individuals and more than 200 organizations in Fort Wayne and beyond are involved in United Front.”

The initiative is earning recognition beyond Fort Wayne, too. In June, the City of Fort Wayne received an All-American City designation from National Civic League, and United Front was highlighted as one of three key projects in its proposal. Headley says United Front has been getting requests to develop similar programs for other cities, too.

“We’re already working on duplicating this model for cities in Illinois and colleges in Ohio,” Headley says. “We’ve developed a model that invites people into challenging conversations.”

***

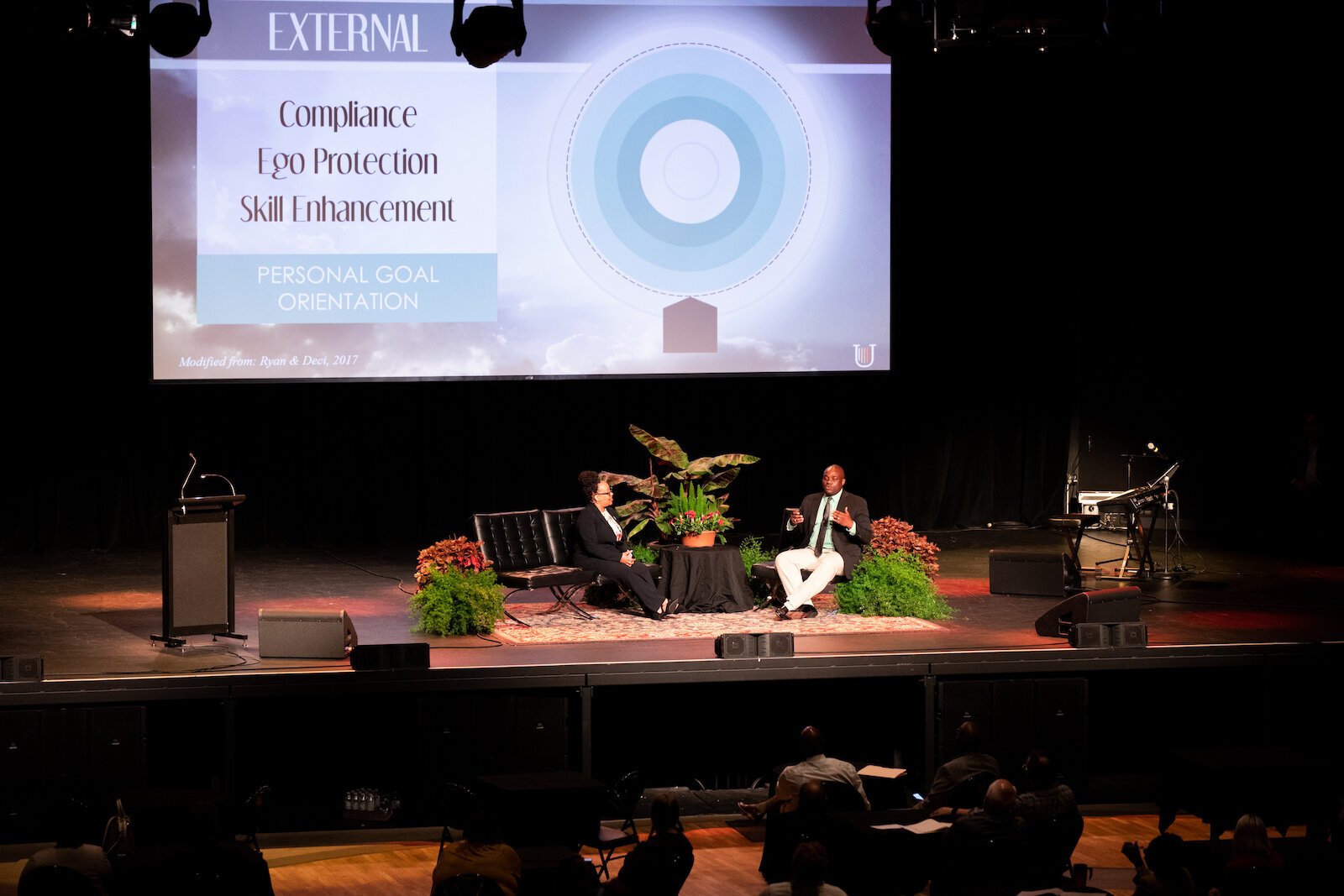

One aspect of United Front’s model that makes it unique is its structure. It offers high-level, conference-like keynote sessions once a month, led by Losambe or a guest speaker. Then it follows these sessions with a series of smaller, highly personalized breakout sessions on Zoom, where people in similar fields process the content together, getting vulnerable about their challenges, biases, and beliefs regarding specific scenarios.

There are separate United Front courses for people working in criminal justice, in the education system, local leadership, frontline responder positions, and as Diversity & Inclusion professionals.

“It’s not only educating people, but also equipping and empowering them to go into their organizations and to do the work themselves,” Headley says. “We are putting Fort Wayne’s leaders in the driver’s seat of their own journey, in one room, and saying: Here’s specifically what implicit bias might look like in your organization.”

During a breakout session on Zoom in early July, about 50 community leaders attend. Losambe welcomes everyone, calling the group a “family,” and walking them through a few situational exercises, in which they have to discuss how they would handle various scenarios in virtual breakout rooms, before returning to the main session to share reflections.

Losambe says United Front’s focus on practical applications and engaging leaders on a personal level allows the program to go deeper than other diversity and racial bias trainings he’s experienced.

“The willingness of people to throw things out and to add things is really what makes United Front function well,” he says.

Both Losambe and Headley recall several times in the past few months when they’ve been stopped by participants at restaurants or public events who say United Front sessions have improved their lives and perspectives.

“We have had a lot of folks, even folks in the local African American community, who have approached us and said, ‘I am expanding my view of racism; I am having more grace and not expecting perfection from the opposite race,’” Headley says. “Some of our leaders in criminal justice in Fort Wayne have also told us the program is impacting their work. The other day, someone said they left a session feeling ‘convicted, not condemned.’ That’s powerful.”

But will conversations and realizations gleaned through United Front create actionable change in Fort Wayne’s community that serves and protects the city’s Black and Brown residents?

This is one question residents, like Alisha Rauch, are asking.

***

Alisha Rauch is the Fort Wayne mother who started last summer’s local protests following Floyd’s murder, in part, as a way to protect her four Black sons. When it comes to programs like United Front, Rauch is skeptical of its intent and its ability to improve conditions for Fort Wayne’s Black and Brown communities.

As cities across the U.S. have responded to Floyd’s murder, there’s been a rush to address long-overlooked racial challenges. Rauch sees United Front as a symptom of “performative,” trend-driven activism, which inspires talk, while upholding the status quo in race relations.

She fears it is diverting dollars and attention away from other potential ways to serve Fort Wayne’s Black and Brown communities.

Rauch and her partner in activism, Daylana Saunders, Co-Founded a group called the ChangeMakers following last summer’s protests, hoping to make progress on matters they and others feel are not being effectively addressed in the community.

Saunders believes the concept of Diversity and Inclusion is too vague to create change in Fort Wayne.

“Diversity can be taught as ‘being inclusive of women,’ as opposed to specifying Black people, who were the bodies and lives lost and put on center stage this summer,” Saunders says. “D&I curriculum buries the real issues that were centralized this summer. United Front’s method for creating this program, privately and partnered with the Mayor and FWPD, is both misguided and disrespectful. There are too many red flags; two of those are that it is not community-led or community-driven.”

On May 29 and May 30, 2020, residents and bystanders in downtown Fort Wayne were forced out of protest demonstrations when police fired tear gas into crowds. The Journal Gazette reports that 97 people total were arrested in two days, and protesters, like 21-year-old Balin Brake of Fort Wayne, suffered serious injuries. Brake’s right eye was destroyed by a tear gas canister, which made national headlines in 2020. Litigation between the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the City of Fort Wayne is still under review.

In August, AP News reports that Allen County Prosecutor Karen Richards prosecuted 50 people arrested after protests in Fort Wayne and dropped charges against 45 others. Five cases of “unreasonable force” were forwarded to the FWPD internal affairs office for review.

***

The FWPD is one group that has been going through United Front’s trainings, using a modified version of the program. Police Patrolman Douglas Weaver says all of the FWPD’s 480-some officers have been participating in United Front trainings since February, utilizing a video-only version of the program, which they can complete on their own time, from their desk or squad car, while they work.

The purpose of this modified program is to prevent taking officers off the streets, Weaver says.

As a part of this specialized United Front program for the FWPD, officers get assigned to watch two video presentations per month, which are about an hour or an hour-and-a-half-long each. Officers are held accountable to watching these sessions by a virtual training system called the Police One Academy, which tracks who has viewed videos and who has not.

In addition to United Front’s keynote sessions, the FWPD also receives video recordings of the program’s Zoom sessions, featuring community conversations. However, they are not live on these calls. Weaver says the officers are processing the content amongst themselves.

“Our officers are discussing it, and it is building greater self-awareness for us,” he says.

Beyond Fort Wayne, the Allen County Sheriff’s Department, which had officers on duty for last summer’s protests, is not participating in United Front yet, according to Headley’s knowledge.

While the FWPD’s video-only participation does remove United Front’s distinctive interactive elements, Headley says his team’s goal in providing this modified option is to make the program as accessible as possible.

“Our other option was to not have the FWPD participate in United Front at all, which was not an option for us,” Headley says. “We will always choose to have our partners participate, while helping us to build the bridge that will eventually get us to our ultimate goal.”

Regarding policing, Deputy Chief Mitch McKinney, who co-manages the FWPD’s Community Relations, says that in addition to the department’s United Front participation, officers have been undergoing procedural justice and legitimacy trainings since November 2013, a year when Fort Wayne experienced its highest homicide rates and received these trainings nationally.

A man of color himself, McKinney leads the trainings in Fort Wayne with each recruiting class since 2013. He says the typical annual sessions are about eight hours long, but the public is welcome to experience a shorter three-to-four-hour version of the training themselves to see what it’s like.

“We have classes on civility, bias, and how races plays into policing,” McKinney says. “We want to be more accessible to the community because that’s what the police department should be about. We shouldn’t always be seen just because somebody calls 9-1-1; we should be a part of the community.”

McKinney is a Republican candidate for Allen County Sheriff, and he hopes to make these trainings county and statewide.

“I’m presenting the class to the Indiana State Paternal Order of Police,” he says. “I want to introduce this to our State Lodge, so everybody is using this schematic to bring community members together to work on facts, why we train, and what we need to do to be better to be advocates in the community. We’ve trained 800-900 people so far, and it’s been very effective for us.”

McKinney says he was at the scene of the protests in Fort Wayne last year on day three, after two days of tear gas, and he was working that day to talk with community members and protesters about the FWPD’s work.

“Nobody should be more upset about what happened to George Floyd than a good cop,” McKinney says. “I’m a Use of Force trainer, and we train officers not to do that. It makes me sick to my stomach to this day.”

***

Joe Jordan, President of the Boys and Girls Club, who is a member of the United Front Initiative leadership team with Headley, Losambe, and other local leaders, says he respects the multitude of ways Fort Wayne’s Black residents are feeling following last summers’ events. He hopes United Front can provide one avenue for residents to develop a greater understanding of race and humanity in Fort Wayne.

The training includes learning paths on implicit bias and microaggressions, stress of minorities, allyship and active bystanders, and difficult conversations.

“Different people have different methodologies to get where we all want to be at,” Jordan says. “At United Front, we’re trying to be bridge-builders to get to where we can value and appreciate each other.”

Headley echoes that sentiment, adding that more work is needed, starting with healing, to make progress on race relations and human relations in Fort Wayne’s community.

“It’s a process, and that process starts with a commitment to go through the process,” Headley says. “We’re not on a journey that is going to take us a couple of nights; we’re on a journey that could take us a lifetime.”

Headley says he and other members of United Front’s team have created the trainings with their own children in mind.

“I have two sons—two black boys who I adore—and I want to raise healthy adults who are going to be equipped to navigate in the world they’re in,” Headley says. “I want to raise my sons to believe: Yes, people have the ability to be evil, but people have the ability to be good, too, and you have to determine who folks are and what they truly believe through careful judgment.”

***

United Front is still in its early phases of development. As such, Headley says his team plans to keep refining their processes by adding greater accountability measures, like course certifications, to the program.

While some United Front participants, like the FWPD, are taxpayer-funded public entities, individuals and business leaders enrolled in the program present other hurdles to accountability on standardizing diversity, equity, and inclusion practices in the city.

Andrew Downs, Director of the Mike Downs Center for Indiana Politics, points out that because many businesses and organizations participating in the United Front initiative are privately owned, they can’t be mandated to implement the training they receive.

“When it comes to a private company, that’s a private entity, so there is a very little the government is going to do to regulate it unless there’s a complaint about a violation of some law,” Downs says.

However, as one way to enhance accountability in the program, Downs suggests United Front or Fort Wayne City Council could ask business leaders and HR representatives who go through the training to report back to City Council about what changes they are making in their organizations as a result of the sessions.

“You could encourage people to approach this as an opportunity to report back—not from an adversarial position, but as a way to share their progress and figure out ways to keep improving,” Downs says. “It doesn’t have to happen at a City Council meeting, but if it does, it carries more weight in the community, at large.”

Headley and Jordan say they’re looking into this option. Ultimately, their goal with United Front is to increase awareness and shared understanding about the underlying effects of race and bias in Fort Wayne.

“We welcome anyone who finds themselves fatigued by dissension and discord to consider participating in our United Front initiative,” Headley says.

NOTE: The original version of this story said United Front’s courses are free. That is incorrect. Program fees are listed on United Front’s website.