SPECIAL REPORT: How Parkview LaGrange is using food as medicine to treat type 2 diabetes

“Farmacy” is an apt word to describe what’s happening in the rural community of LaGrange.

When Jeremy Hoover of LaGrange County was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes about two years ago, he didn’t know much about the disease.

What he did know was what he liked to eat and what he did not like to eat.

“I was a meat and potatoes, fried foods kind of guy,” Hoover says. “I would hardly eat vegetables at all; I didn’t really think that I liked them.”

Today, his diet has changed by choice. Hoover regularly eats vegetables like broccoli and cauliflower, using them to supplement carbohydrates like noodles and potatoes in his meals. These healthy lifestyle changes are largely thanks to a new program at Parkview LaGrange Hospital called the Food Pharmacy.

Instead of treating type 2 diabetes patients with medication, it treats food as medicine, prescribing them with a healthy dose of eating options, a regimen of cooking classes to prepare the food, and regular meetings with other participants and Parkview specialists to support long-term lifestyle changes.

Adam Gehring, a registered dietitian at Parkview LaGrange Hospital, directs the program, which went into its second year in February 2019 after a highly successful pilot program in February 2018.

Stories like Hoover’s are good examples of the Food Pharmacy program’s potential.

When it comes to type 2 diabetes, a lack of information and accessibility to healthy lifestyles can be a major culprit in worsening conditions.

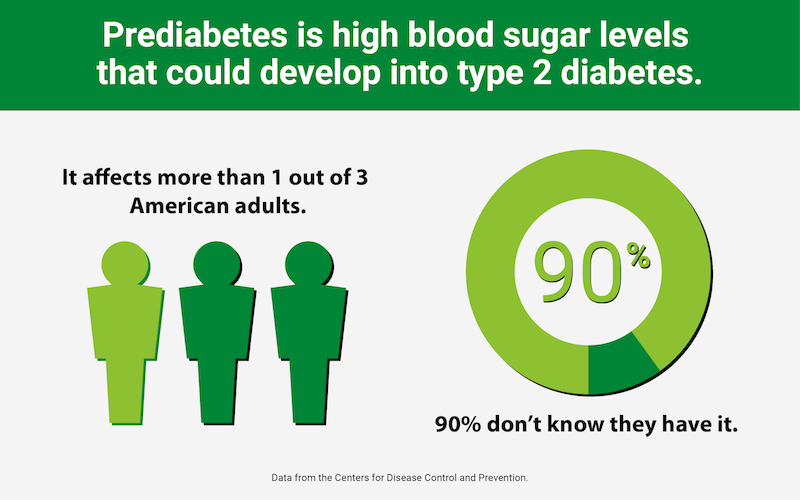

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that one in three American adults have what is called “prediabetes”—or high blood sugar levels that could develop into type 2 diabetes, and 90 percent don’t know they have it.

However, once the disease escalates and medical intervention is needed, it becomes costly and burdensome to patients, healthcare systems, and economies alike.

In fact, the American Diabetes Association estimates that the overall cost of diagnosed diabetes has risen to $327 billion.

But in LaGrange County, change is underway to challenge these statistics, going back to northeast Indiana’s roots in farm-fresh vegetables.

***

“Farmacy” is an apt word to describe what’s happening in the rural community of LaGrange.

Gehring says the conditions that lead to type 2 diabetes often come down to what we eat and how often.

“The things that we’re eating that aren’t typically helping are an excessive amount of carbohydrates, an excessive amount of calories, an excessive amount of eating times, and not limiting our portions,” he says.

What makes Parkview LaGrange’s Food Pharmacy so unique is that it was designed as a non-pharmaceutical approach to treat diabetes—and that’s especially good news for the rural cities and towns of northeast Indiana.

A 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment released by Parkview Noble Hospital identified both diabetes and obesity as significant health concerns in the region.

In LaGrange County alone, 11.8 percent of residents have been diagnosed with diabetes, according to the report, and 34.2 percent of respondents fell under the medical definition of obese, having a body mass index greater than 30.0.

“In the pharmacy field, we always advocate ‘non-pharm’ interventions,” says Ross Robison, a Parkview LaGrange Hospital pharmacist who is involved with the program. “‘Non-pharm’ essentially means non-drug interventions like diet, exercise, and lifestyle adjustments. If those don’t get you to your health goals, then we add in medication.”

In the case of Food Pharmacy, “non-pharm” means a food intervention, encouraging residents to eat more of the fresh vegetables they might find at local farmers markets.

When it comes to specific food types that commonly cause obesity and diabetes, Gehring cites an excess of desserts, breads, foods made from potatoes, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

“It really comes down to the balance of what we eat—how much we’re eating, when we’re eating, portion size, and what we’re eating,” he says. “Protein with carbohydrates and vegetables is a very healthy way of eating.”

***

While the Food Pharmacy is more than a diet and a cooking class, learning how to prepare healthier fare from recipes is a major component of the program, Gehring says.

During the pilot, a group of 10 participants or “students”—all of whom met requirements for inclusion and were referred by their primary care doctor—met together as a class 18 times in a span of six months. During that time, students received education and care from physicians, dietitians, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals, as well as educators.

Each participant underwent lab tests, was weighed, and had their vital signs checked at the beginning, middle, and end of the program.

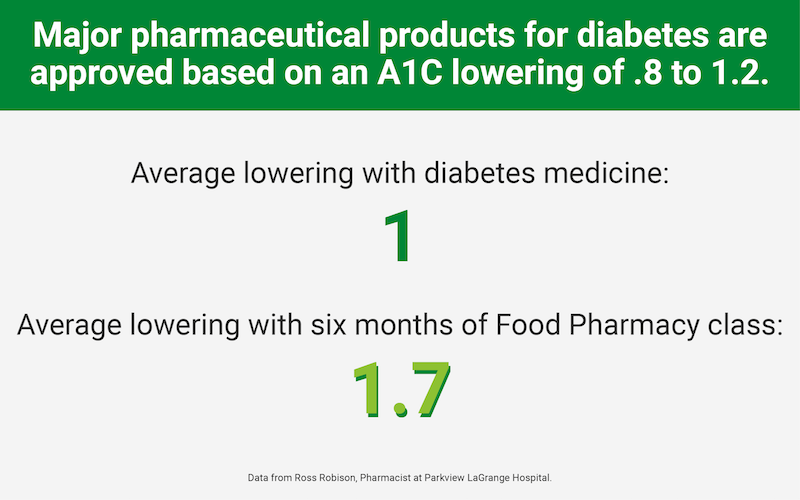

The results have not been found wanting. At the end of the pilot program last year, Food Pharmacy participants lost an average of more than four pounds, saw lower hemoglobin A1c, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol numbers, and enjoyed an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels—the good kind, Robison notes.

“The fact that we lowered A1c (a signifier of average blood sugar levels) by 1.7 is pretty significant,” he says, stressing the importance of participants being partners in fighting their disease.

“Patients want to understand their disease state, and they want to be given tools to be able to take ownership to help manage this disease state,” Robison explains. “They’re very encouraged by a program like this.”

This is all great news for Dr. Jamin Yoder, a Shipshewana family practice doctor, who is both involved with the program and refers patients to it.

“We look at the results of them changing their diets and exercise habits and how this affects long-term outcomes for diabetics,” Yoder says. “They then know that they have a disease process and have foods they are unable to eat, and they can make healthy choices.”

Gehring says it’s about dietitians, doctors, and specialists showing participants that they care about them and their conditions, too.

When he starts working with patients who have newly been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, he starts by simply listening.

“The first thing that I do is I let them talk,” Gehring says. “I try to ask them a few questions just to get to know them a little bit better and build that rapport, because honestly, they’re not going to do anything that I say if they don’t think that I care.”

Hoover, who at first wasn’t overly excited about Food Pharmacy being conducted in a group setting, says he wasn’t the only one to be quiet and feel awkward at the first gathering. However, it didn’t take long for him to realize the benefits of having other people in the program who were in similar situations.

“Everybody kind of opened up, and we were much more comfortable talking about issues that we have with our diabetes and questions that we had,” he says. “That made it a lot easier.”

From a physician’s standpoint, having patients learn in classes is helpful, too, Yoder says, because it allows them to generate their own momentum in developing healthier lifestyles.

“The story that I think that is helpful is the people starting to get to know each other and spend time together,” he explains. “They start coaching each other and not relying so much on the experts there to tell them what to do.”

Learn more

Food Pharmacy is open to all physicians—to refer their patients—in the LaGrange County area. According to a Parkview Health spokesperson, there have been discussions about implementing a Food Pharmacy program elsewhere in the Parkview system, although a startup date has not been determined.

To learn more, visit the program’s web page.

This Special Report was made possible by Parkview Health.