The urban expressway not taken: Exploring the history and future of Fort Wayne’s roadway system

Unlike many other growing cities, Fort Wayne does not have an interstate running through its core. Will this hinder or help its future growth, and what's next?

The City of Fort Wayne has traversed through several overland transportation systems since its founding. From the lying of plank roads to the paving of new interstates, the area has adapted to growing transportation needs. But unlike many other growing cities, Fort Wayne does not have an interstate running through its core. Will this hinder or help future growth?

The Northeast Indiana Regional Partnership has a “vision of becoming a region of 1 million people” by the year 2030, and transportation certainly plays a role in the livability of a community and its access to talented individuals. So what is the history of Fort Wayne’s roadway system, and what can we do to improve it?

According to an article by local historian Tom Castaldi, in the mid-1800s, crews constructed “plank roads” to ensure smooth travel into Fort Wayne via carriage. Companies laid wooden planks between Fort Wayne and other population centers to draw people to the “swamp-locked” city. These wooden planks allowed for the wheels of a carriage to roll smoothly across long distances. The plank roads were ultimately replaced with different materials, and most remain highly trafficked today. These include Bluffton Road, Goshen Road, and Lima Road, to name a few.

Formally dedicated in 1913, the Lincoln Highway became the first “auto trail” across the U.S. The Lincoln Highway Association, a non-governmental organization, maintained the route which used a number of smaller roads to traverse the nation from New York to San Francisco. The Lincoln Highway intersected Fort Wayne through each realignment of the trail, providing citizens with a viable and safe option for long-distance travel. Similar auto trails sprouted up around the U.S., but were superseded by the new U.S. Numbered Highway System in 1926. This marked the transition from highway associations to government-managed highway systems.

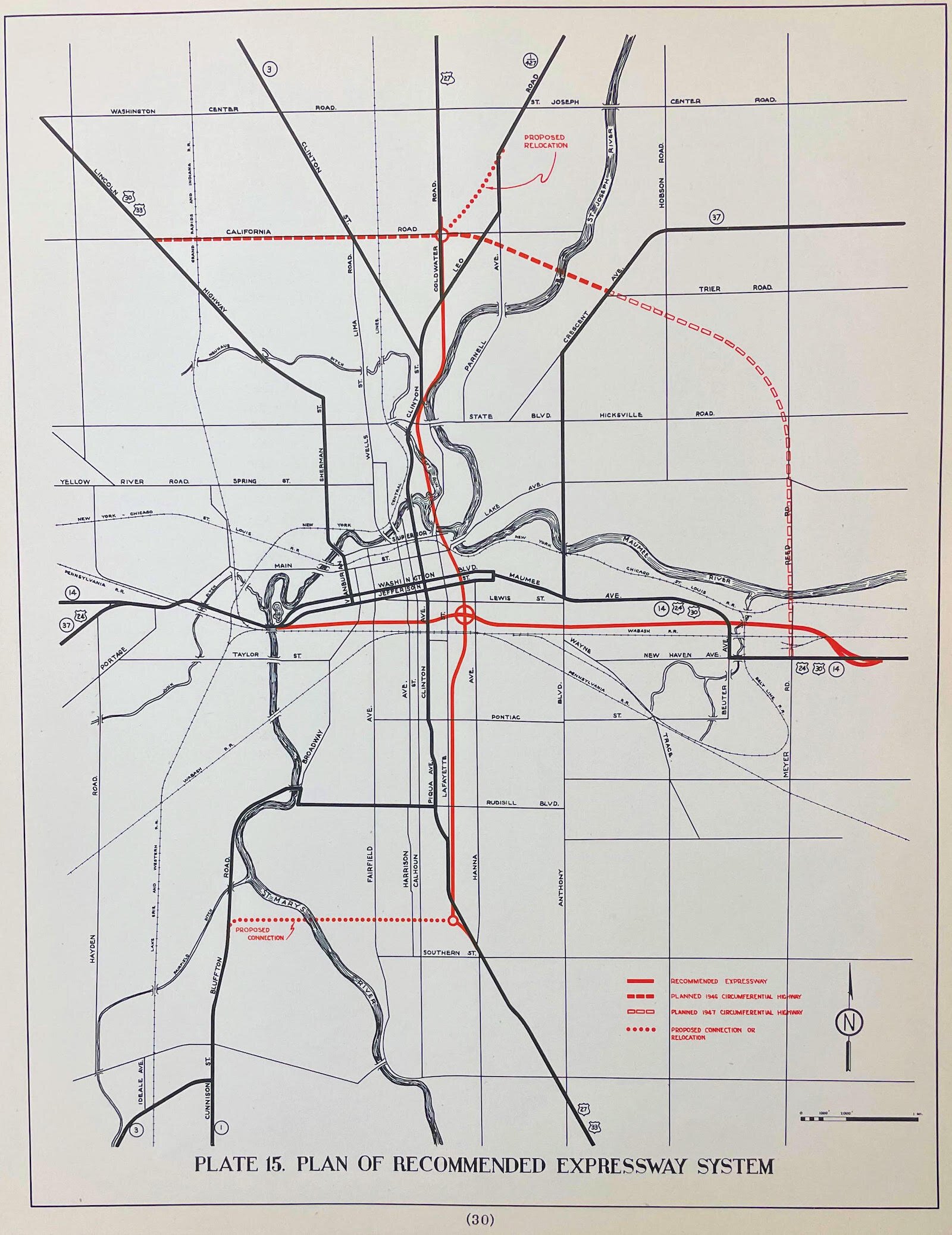

The State of Indiana maintained a number of highways in Fort Wayne until the introduction of the U.S. Numbered Highway System and continued to maintain several after the federal expansion. After the federal system had been in place for several decades, the State Highway Commission realized Fort Wayne’s infrastructure needed upgrades. One of these proposed upgrades ultimately became Coliseum Boulevard, known to older residents as “the bypass.” This northern bypass around the top of the city map was built to alleviate downtown traffic, and it was the only major result of a failed 1940s highway plan.

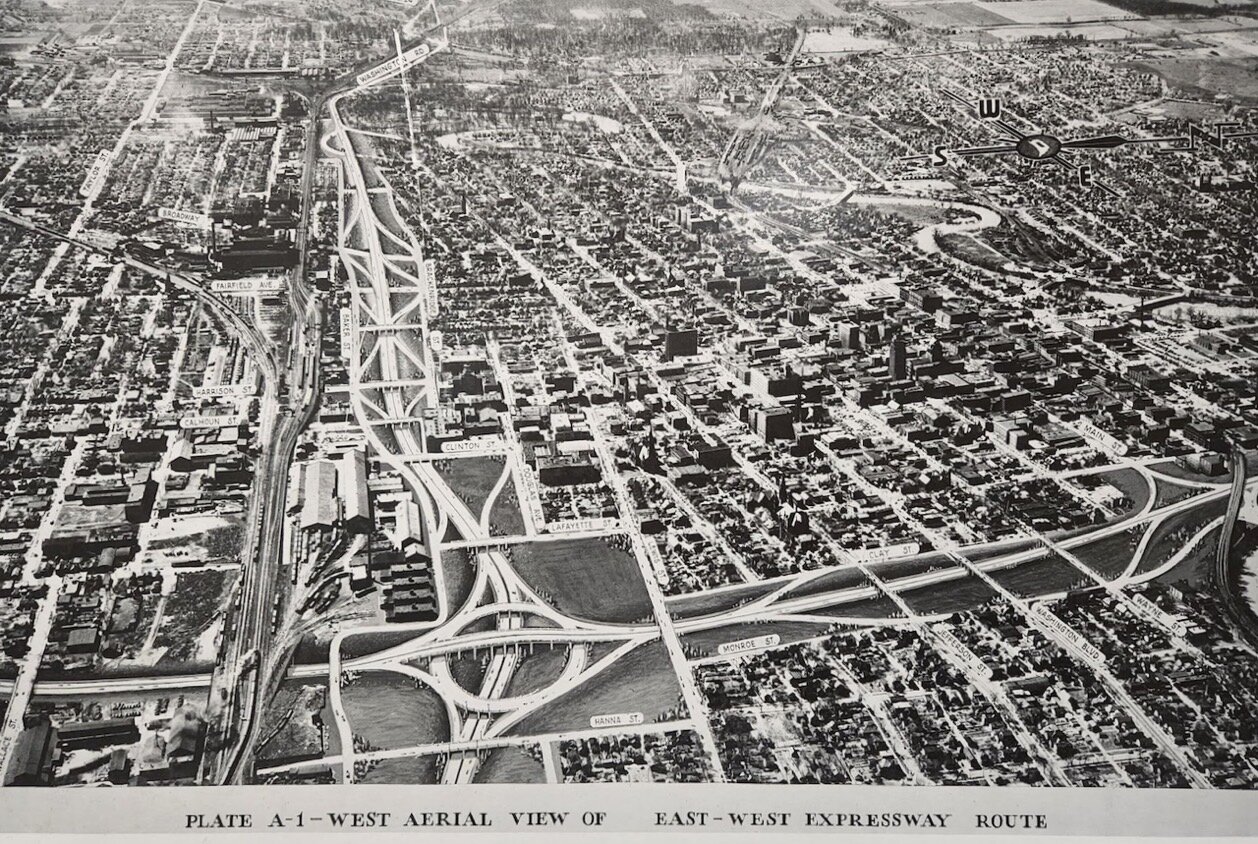

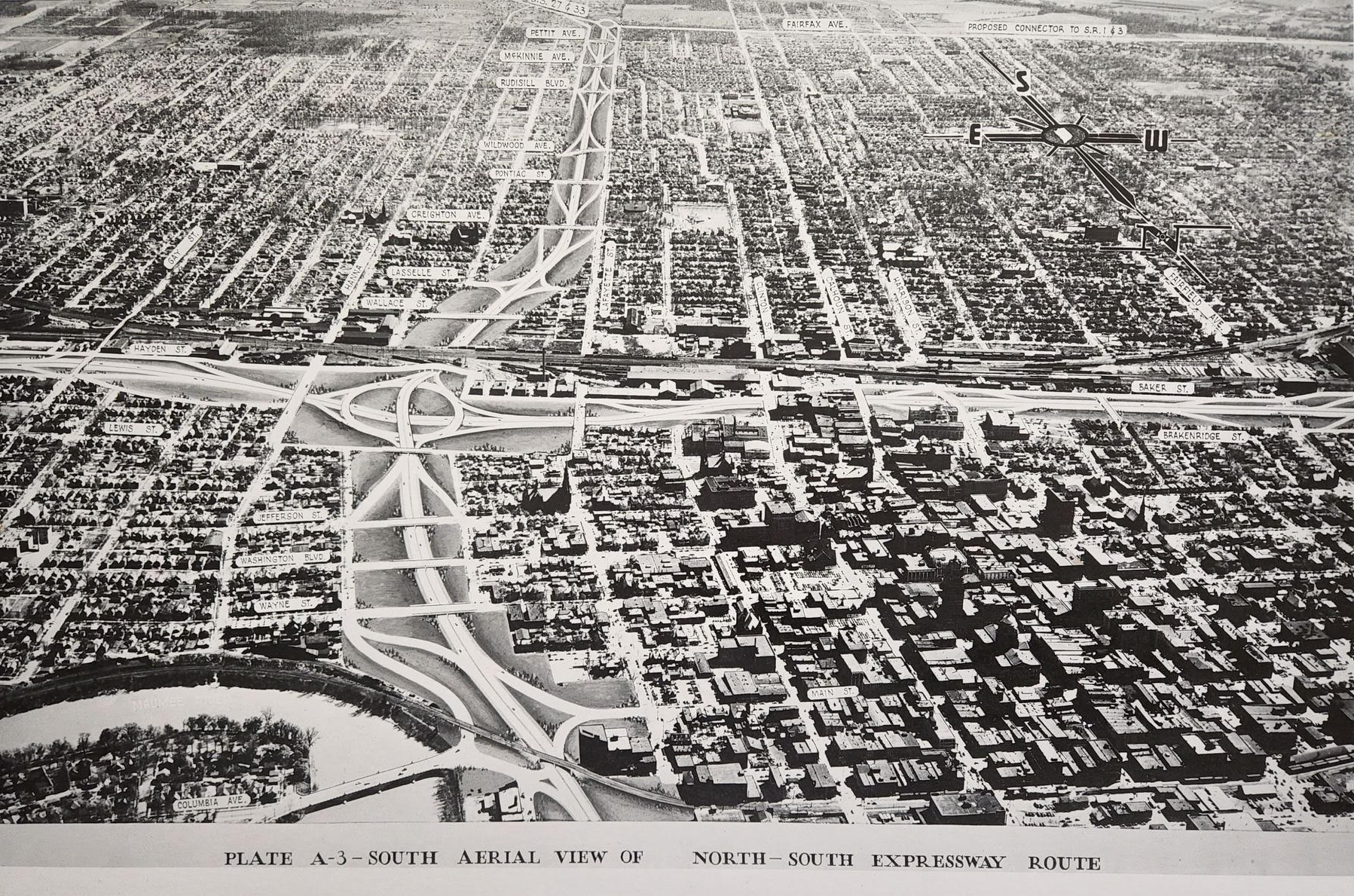

As a part of national efforts to reexamine traffic issues following World War II, the State Highway Commission of Indiana proposed in 1946 that two expressways be built through Fort Wayne. One would intersect the city from north to south, the other east to west. They examined the routes that vehicles took through Fort Wayne and attempted to replicate those trips in the pathway and connectivity of these expressways.

Obviously, this never came to fruition. A referendum was held on Nov. 5, 1947, and citizens voted overwhelmingly against building the expressways, according to a newspaper article. A number of factors could have contributed to this rejection. The City of Fort Wayne’s Historic Preservation Planner Creager Smith says the highway’s cost and citizens’ dissatisfaction with then-Mayor Harry Baals could have resulted in the failured initiative. (Mayor Baals did, however, elevate the railroad tracks downtown to allow for free flowing traffic underneath passing trains when he returned to office in the 1950s.) Smith also points to the potential destruction of more than 1,500 buildings, many of them historic, as an issue contributing to the downfall of the commission’s highway proposal.

“At that time, they had not really yet developed the idea of taking highways around cities,” says Smith. “They were still thinking in the terms of railroads: That the best situation was to take a highway through a city for access to the city.”

“By comparison,” he adds, “I-69 probably took down some buildings, but it would have been trivial compared to 1,536 buildings to build something like this.”

Race also may have played a factor in the failed expressway route. Smith points to an article that highlights this concern, noting the proposed route would have displaced many of the city’s communities of color. The article claims that the “truth of the matter was that the Blacks (Negros) [sic] would have had to be relocated and no one wanted us.”

In recent months, U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg has extensively discussed racially motivated highway decisions during the building of interstates across the U.S. NPR reports that race and class issues have influenced transportation and urban planning to the point that highways were intentionally routed through neighborhoods according to race and/or income.

“Very intentionally, highways were sometimes built right on the formal boundary lines that we saw used during racial zoning,” ACLU President Deborah Archer tells NPR. “Sometimes community members asked the highway builders to create a barrier between their community and encroaching Black communities.”

There is inconclusive evidence that Fort Wayne’s own failed expressway was intentionally routed through predominantly Black neighborhoods. But this perception in the 1940s likely added to pre-existing concerns surrounding the plan.

Regardless of its intentions, Fort Wayne’s decision to forgo the central expressway might have ultimately aided the city’s efforts to reinvest in its urban core. Data shows that cities with even one interstate highway through their core have expedited division, suburban flight, and sprawl in costly ways leaders are still seeking to reverse. As these systems age, many cities from Portland to Chattanooga are deconstructing segments of their urban highways to make way for less obtrusive, more inclusive forms of transportation, like public transit, walking, and cycling. Fort Wayne may have lessened some of these challenges locally by not routing expressways through its urban core in the first place.

Beginning in the 1950s, Fort Wayne’s infrastructure received its much needed upgrade when interstate highways were introduced as a result of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s national defense plan. One interstate and one auxiliary interstate, I-69 and I-469 respectively, were added to Fort Wayne over the next several decades. I-69, while initially tracing the Northwest edge of the city, now cuts through Fort Wayne as the city grew around it.

Although initially intended as a Southern bypass for US-24, I-469 ultimately completed the interstate loop around Fort Wayne. The completion of this route altered the map at the heart of the city. Highways 24, 30, and 33 were moved from downtown to I-69 and the new auxiliary route. State Routes 1, 3, 14, and 37 were terminated near city borders, and 930 was introduced to the city’s Northern residents. This meant semi trucks had an uninterrupted route around the city, and residents in the Northeast quadrant had easy access to I-469’s parent interstate.

Even with the addition of the auxiliary route, efficient travel through and around Fort Wayne is not without its roadblocks so to speak. A growing population and booming downtown means more traffic is flowing through the core of the city. And as desire for multiple modes of transportation grows, officials have to take into greater consideration stakeholders beyond drivers, too. A widened road downtown could mean smaller sidewalks for pedestrians or no bike lane for cyclists. More efficient routes, like a revival of the failed expressway, could mean the destruction of historic buildings and neighborhoods, as well as the displacement of citizens from their homes.

Safety is another concern. In the absence of a central expressway, exisiting infrastructure, like US-27, which runs through downtown as Lafayette Street, functions as the fastest option for travelers. There are residential lots along this highly traveled route, too, which can cause issues with safety and standard of living.

With these stakeholders in mind, what could improve traffic flow as the region grows? In recent years, Fort Wayne and other cities have seen expanded use of traffic circles, known here as “roundabouts.” According to IN-DOT, roundabouts have a 30 to 50 percent increase in traffic capacity than a typical intersection. Additionally, there are fewer annual costs, significantly longer service life, and a 76 percent reduction in injury crashes. And roundabouts are just one option to improve efficiency at existing intersections.

IN-DOT plans to improve intersections and general travel along Ludwig Road near the interstate, and IN-DOT will continue to increase the flow of traffic at the I-469/US-24 interchange, portions of which have already been completed. This includes the elimination of a stoplight at the interchange, which now allows traffic to freely merge onto the highway.

Changes over the next several years could include retiming traffic lights, adding lanes, or converting existing intersections to more efficient, safer exchanges. Finding a solution to stop-and-go traffic on Coliseum Boulevard, adding more slip lanes, or even just marking turn lanes more clearly may vastly improve commute time and safety.

While the future of travel remains to be seen, it’s ever-important to remember the past.

This story is part of a series on the 8 Domains of Livability in Northeast Indiana, underwritten by AARP.