Getting to know the ‘ignored legacy’ of Black leaders in Fort Wayne history

"Fort Wayne’s black history is not fully known.”

Across the U.S., Black History Month every February is often commemorated with quotes and images of the legendary Civil Rights advocate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But in 2021, as the global Black Lives Matter movement asks cities to reconsider the role of race and racism in their past and present—not just during Black History Month, but every month—there’s a new urgency to remember and recognize Black leaders in local history.

Along with King’s monumental contributions to national and global concepts of equity, equality, justice, and civil rights, there are other—often less prominent—Black men and women who have innovated and sacrificed on the frontlines of history. There are leaders who have been breaking down racial barriers in cities, like Fort Wayne, for decades and leaving a legacy that is all too often overlooked.

Reviving the stories of these “ignored” history-makers is the spirit of the essay, Illuminating an Ignored Legacy: The African American History of Fort Wayne by the late-Hana Stith in the 2006 book History of Fort Wayne and Allen County, Indiana, 1700-2005.

Throughout her essay, Stith shares the stories of several important figures in local history, ranging from the city’s first Black police officer to the creator of its first Black minor league baseball team.

But while Fort Wayne’s Black innovators and creators have been numerous since the city’s founding, many details of their lives have been lost in time. For generations, Black history was not valued in American society, and there were limited opportunities for Black families to preserve it.

“Early public records and documents omitted (Black residents’) significant developments and accomplishments, and until recently, few written histories of Fort Wayne even acknowledged that African-Americans were in existence here,” Stith writes. “As a result, Fort Wayne’s black history is not fully known.”

That’s the challenge facing Fort Wayne’s African/African-American Historical Society Museum (AAAHSM). Celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2021, the downtown museum exhibits Black and African American history in Allen County from 1809 to present day, and it houses the area’s largest public collection of African art.

A small volunteer staff of John Aden, Ph.D., and Leah Reeder, oversee the museum, serving as docents and curators for its collection of photos, documents, and artifacts housed at 436 E. Douglas Ave. But the physical elements of the collection are only a portion of the knowledge it preserves.

“So many of these narratives are anecdotal,” Aden says. “They were passed down through oral history.”

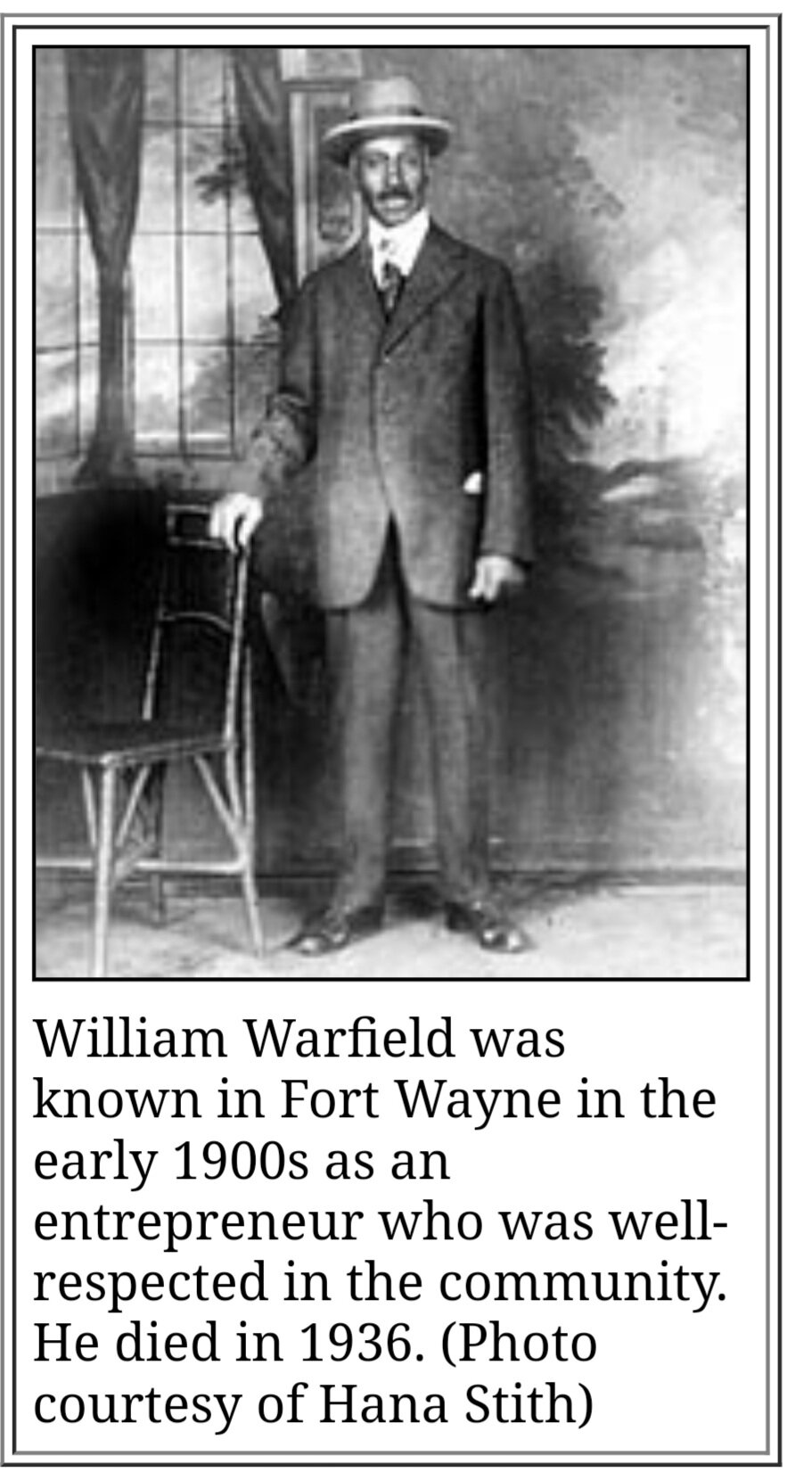

One local public figure whose life and legacy breaks this mold with extensive records is William E. Warfield, one of the most prominent Black individuals across the Midwest in the early 20th century. Warfield was perhaps Fort Wayne’s first Black real estate investor and newspaper founder who owned a 21-bedroom mansion (now torn down) on the same street as the current AAAHSM.

“He shows up in the 1880 census in Maysville, KY, as a person of biracial ancestry, living in the white part of his family’s household, with his birth mother living in the house next door,” Aden says. “In 1880, the Civil War had been over by about 15 years, but a lot of Americans don’t realize that even though slavery wasn’t legal in Kentucky, slaves were still kept there, as a Mason-Dixon Line state.”

After arriving in Fort Wayne around the age of 20 in 1890 after a seminary stint on the East Coast, Warfield worked odd jobs as a waiter and janitor. His earnings (and suspected family wealth) helped him purchase several properties around town, which he used as boarding rooms for Black travelers who could not stay at traditional hotels and motels at the time.

From the year Warfield purchased his massive Douglas Street home in 1909 to his death in August 1936, he kept meticulous records of his financials, as well as his thoughts on current events in Fort Wayne and beyond. The AAAHSM has preserved these records in his Warfield Diaries, now available selectively online through the Allen County Public Library’s Genealogy Center.

“Some of Fort Wayne’s most accurate and amusing history is written in their pages,” Stith writes.

While much of Warfield’s life has been documented, certain aspects—like how he afforded seminary in the late 1800s, or how he secured a $20,000 loan from a Fort Wayne bank in the 1910s—remain shrouded in mystery, Aden says.

Since Warfield also had white American ancestry, and he had a wealthy white step-brother, Aden suspects his brother might have sent him money occasionally or co-signed on loans, but the historical record isn’t clear.

“In his diary, there’s this shadowy figure who shows up from time-to-time and is probably his step-brother,” Aden says. “But Warfield himself is an interesting figure. I think a movie could be made about his life.”

Among Warfield’s writings and poetry, he penned the song, “We Love Old Fort Wayne,” which was played at the grand opening of Lincoln Tower Bank in 1930.

“When I do a tour, I play a version of my aunt playing, ‘We Love Old Fort Wayne,’ for guests,” Reeder says, noting that tours of the museum have been put on hold during COVID-19.

Even so, she and Aden are staying busy in these historic times, collecting the obituaries of local Black residents for the Genealogy Center, moving documents like the Warfield Diaries online, and working with aging Black residents in Fort Wayne to preserve their legacies for future generations.

They’re also working with the Genealogy Center on its African American Gateway project, which is creating a growing resource for African American research in the U.S., Canada, the Caribbean, and other countries.

“It’s sometimes challenging to do all of this work in addition to our day jobs,” Aden says. “But there are some real opportunities here.”

Along with early civic leaders like Warfield, several African American residents from Fort Wayne have made history in national and international sports.

“Fort Wayne has produced more NFL players than almost any other city in the country,” Aden says.

As an example, he points to NFL Hall-of-Famer Rod Woodson, who went on to be an analyst for the NFL Network, the Big Ten Network, and Westwood One, before coaching in 2014.

“He went to Snider High School in the mid-80s, and he was a world-class sprinter,” Aden says. “He could have had an Olympic sprint runner career and been successful in that, too.”

Along with Woodson, a prominent Canadian Football League player has roots in Fort Wayne: Johnny Bright, who was born in the city in 1930 and died in 1983.

After becoming a three-sport (football, basketball, track and field) star at Fort Wayne’s racially integrated Central High School, Bright attended Drake University in Des Moines, IA, and was the first African American allowed to play on their team.

“Not only did he play Quarterback, but also Running Back,” Aden says.

Throughout Bright’s college career, he became one of the best players in the country. But he suffered a racially motivated attack during a game at Oklahoma A&M University in 1951, which caused him to pursue a career in the Canadian Football League (CFL) instead of the NFL—and to change the face of football forever.

At the time, football helmets only had a single bar across the jaw, and during that Oklahoma game, players were instructed by their coaches to “get Johnny Bright” by reaching through his helmet to break his jaw.

Coincidentally, Life Magazine reporters were on the scene with video cameras and captured the entire incident on film, which can still be viewed today.

“It was really a scandal because Johnny was so talented,” Aden says. “Even with a broken jaw, he was still making 200-yards from scrimmage, and no one had done that before.”

After immigrating to Canada, Bright became a CFL star, breaking records and inspiring namesakes, like Johnny Bright schools and parks.

“He’s also the reason why you have football face masks with a cage on them now,” Reeder says.

Here are a few Black leaders from Fort Wayne history you should know, as described by the African/African-American Historical Society Museum, and the essay Illuminating an Ignored Legacy: The African American History of Fort Wayne by Hana Stith.

William E. Warfield, Fort Wayne’s first Black real estate investor and newspaper founder

William E. Warfield is considered Fort Wayne’s first Black real estate investor—and the city’s “leading Black citizen” in 1913. At the time he lived in Fort Wayne during the early 1900s, Black people could not stay at any of the local hotels or eat in local restaurants, but Warfield’s life and legacy provided for his neighbors in need.

Born in Maysville, KY, in 1870, Warfield earned his certification to teach at seminary in Washington D.C., but he did not want to become a teacher, Stith writes. Instead, he worked as a waiter in Fort Wayne’s Randall Hotel and later became self-employed, picking up odd jobs as a janitor.

Warfield married his wife, Edna, in 1898, and had two children with her in their house on Grand Avenue. Then in April 1909, the Warfields purchased a high-class, 21-room mansion at 450 E. Douglas Ave., then known as Montgomery Street, and they became the first Black family to live on the street. Stith says they not only purchased the home to be their primary residence, but also to provide quality boarding rooms for other Black residents and traveling workers in Fort Wayne, who had nowhere to stay when they came into town as service workers for the railroads, due to segregation.

Over the next several decades of his life, Warfield acquired many properties around town, which he turned into rooming houses: 501 E. Brackenridge St. (Holman St.), 1618 S. Calhoun St., a farm on Bass Road, and a property across from Southgate Plaza.

“Sometimes they wouldn’t let him buy properties because of his color,” Reeder says. But he also had a good lawyer in H.G. Hanna.

Along with his real estate investments, Warfield was an active member of local public life as a writer, poet, composer, and journalist. He composed the song “We Love Old Fort Wayne,” and published the city’s first Black newspaper, The Vindicator, which was among about 30 other Black newspapers of the time, Aden says. Warfield was also a regular contributor to the mainstream local newspapers, writing opinion pieces on local issues.

For generations, Warfield’s legacy and thinking has been well-preserved in his meticulous diaries, dating from January 1909-August 1936, when he died. His diaries detail his financial records and personal experiences on everyday issues, both locally and nationally. You can find the Warfield Diaries online or in the collection at the African/African-American Historical Society Museum.

Edna Warfield and Warfield’s sister, prominent local women of the early 20th century

“Warfield’s story isn’t just his story,” Aden says. “It’s also the story of his wife, Edna, and his sister.” Edna Warfield and Warfield’s sister (name unknown) were prominent local women of the early 20th century.

“Edna was active in the community,” Reeder says. “She also had some sort of wealth on her own because they were both involved in the purchase of their property. But we don’t know much more about her beyond that.”

In his diaries, Warfield frequently and dotingly mentions his sister, who he wrote letters to every day before she eventually moved to the Summit City to live with him.

“When I’m leading tours at the museum, I joke about him and his sister having a great text messaging relationship,” Aden says. “They were particularly close.”

Edna Warfield is buried next to William E. Warfield in Jordan Crossing, which is the African American section of Fort Wayne’s Lindenwood Cemetery.

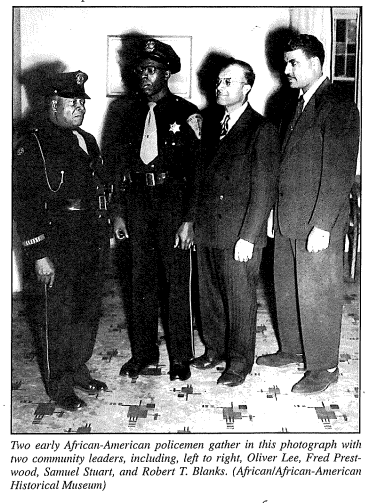

Arthur Williams, Fort Wayne’s first Black male police officer

When Arthur Williams hitched a ride by rail from Fayetteville, NC, to Fort Wayne in the early 20th century, he found work for himself along the way as a chef and chauffeur.

Upon his arrival in town, this experience helped him land a position as the Fort Wayne Police Department’s paddy wagon driver, and eventually, the city’s first Black police officer, when the Black community petitioned the City of Fort Wayne to hire an African American law enforcement officer in 1917.

Stith writes that Williams’s “good reputation” earned him his job on the police force, where he eventually became a patrolman, walking predominantly Black neighborhoods on the city’s Southeast side from Hanna and Hayden Streets to Brackenridge, Eliza, and Lafayette Streets.

In his day, Williams was well-known around town, not only as a cop, but also as the operator of a local dance hall and skate center.

He served on the police force until he died in 1942, and was respected as a “tough cop,” but he was not allowed to arrest white people.

Laura Jackson

Laura Jackson was the first female Black police officer in the city.

“Her story is fascinating,” says Reeder, who notes that the area around the Warfield home stretching all the way down to Indiana Tech’s campus was within her patrol beat.

Like Williams, Jackson was also not allowed to arrest any white residents, Reeder says.

“Even so, she’s known for breaking up a pretty prominent fight in the oral lore of the period, so she was a local fixture,” Reeder adds. “She carried a billy club and made arrests.”

Jackson served on the police force from 1928-1931.

Carl Wilson, a prominent Black entrepreneur

Carl Wilson was a true entrepreneur of the early 20th century. When he confronted a challenge, he created a business to solve it.

Born in Vincennes, Indiana, in 1895, he moved to Fort Wayne in 1917 at the age of 22. He had left home at the age of 14 and found himself “dealing in some illegal activities” for a short time before deciding to legitimize his business ventures, Stith writes. His first business in Fort Wayne was a pool room on Culbertson Street. Once that was going, he moved his brothers and mother to the Summit City and built a home for the family on McKinley Street near Culbertson. But his home experienced challenges with mice and rats.

As a way of solving his own challenges, Wilson founded his second business, the Fort Wayne Exterminating Company, in 1929, with a white business partner who died in 1932. Even throughout the Great Depression, Wilson’s company grossed more than $50,000 annually, serving many of the city’s large downtown businesses, as well as private residences.

An avid fisherman, Wilson often traveled Northeast Indiana, seeking places he could rent boats and fish without racial problems. He eventually found a spot at Fox Lake near Angola, where he purchased land in 1930 and added roads and three cabins: Sky Chick, Wilson’s Lodge, and Shangri-La.

“Many Black people from Fort Wayne and Detroit vacationed at Wilson’s Fox Lake resort properties, fishing and attending large summer picnics sponsored by Wilson,” Stith writes.

In 1935, Wilson opened “Wilson’s Chicken Shack,” a restaurant specializing in southern fried chicken.

“People of all color, from all walks of life and from local and surrounding communities came to eat at ‘Wilson’s Chicken Shack,’” Stith writes. “Wilson’s wife, Mamie, managed the newly opened restaurant while Wilson continued seeking other new profitable businesses.”

While Wilson was a prolific businessman, he died before he turned 50-years-old, killed in a car-train accident while crossing the Wabash Railroad tracks on his way to Marion on the evening of October 2, 1942.

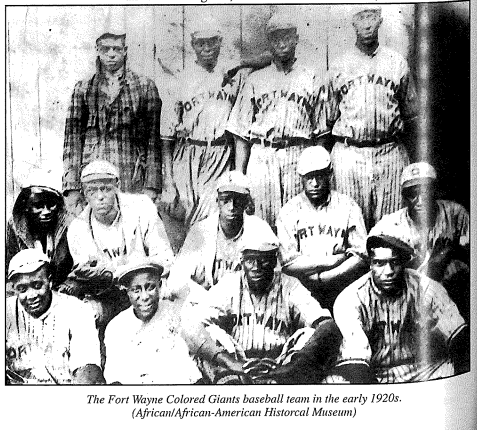

Moses Taylor, the visionary behind Fort Wayne’s first Black minor league baseball team

You know the Fort Wayne TinCaps, and maybe you remember the Fort Wayne Wizards. But what about the Fort Wayne Colored Giants?

In 1920, Moses Taylor’s passion for the sport and his Black community in Fort Wayne inspired him to own and manage the city’s first Black semi-professional baseball team, “selecting as players young men of outstanding skills who had played on church, sandlot, and ‘pickup’ teams,” Stith writes.

Taylor was born in Selma-Anderson, Alabama, in 1882, and moved to Fort Wayne ahead of his family in 1911 in search of work. He married and lived in a house at 416 Helen St. (now Dahlman Ave.). In his spare time, he began playing baseball with members of his church and competing with other Black teams formed by area churches and communities as far away as Muncie, Indiana.

When Taylor and a team of young Black men started the Fort Wayne Colored Giants, they didn’t have a regulation field to play on, so they played in vacant lots around town, sometimes requiring them to cut the grass before games.

Eventually, Taylor secured their home field diamond at the site of the present-day Centlivre Village apartments. As the Colored Giants’ popularity grew, baseball games became a staple in the local Black community on Saturday afternoons where young and old alike would often enjoy the sport together over picnics and root for their favorite players. Each game, there was no admission charge, but the team would pass around a hat to cover the costs of the traveling team’s expenses.

Sadly, financial challenges forced the Colored Giants to fold in 1929 when their bus broke down on the way to play a game in Pittsburgh, Penn. Most of the men, including Taylor, had to stay in the Pittsburgh area to find work there.

Taylor later created another team called the Pittsburgh Mystics, and before his death in 1948, he lived to see Jackie Robinson break into the major leagues.

Learn more

Follow the African/African-American Historical Society on Facebook.